These Eyes… February 16, 2008

Posted by Chuck Musciano in Technology.Tags: History, Interfaces

add a comment

I am a huge fan of mobile devices. I was one of the first people to use a Casio Zoomer back in 1992 and moved on to Palm devices in 1998. I recently made the Great Conversion to a Blackjack smartphone and upgraded to a Blackjack II last November.

I love seeing what new things you can do on these devices, and am always willing to try new tools and applications on my phone. But there is a limit. Some things were not meant to be done on a phone.

The fundamental problem with phones is that the display can only convey so much information. As tools get more and more sophisticated, it seems that the designers are trying to display more and more information on the display. Microsoft seems intent on running the entire Office suite on my smartphone, and phone browsers struggle to handle the complex content of full web pages.

I finally realized why this is happening. The people designing and building these tools have 25-year-old eyes. Many of the people using these tools have eyes that are… much older. Tiny little sharp letters and itty-bitty icons work great for young users. They are completely wasted on us more mature technophiles.

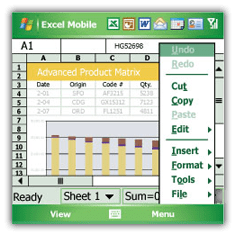

Have you ever tried to use Mobile Excel? Somehow, being able to see five or six cells of a spreadsheet at once leaves a bit to be desired from a usability perspective. Even as tools get more sophisticated in their rendering capabilities (the latest crop of zooming browsers is very cool), there is still only so much you can see at once on the screen. Even when I zoom out until I can just barely read the text on the screen, I still find myself panning back and forth just to read a single text flow in a document. Attempts to reflow the document often break the layout and make the document difficult to understand.

Have you ever tried to use Mobile Excel? Somehow, being able to see five or six cells of a spreadsheet at once leaves a bit to be desired from a usability perspective. Even as tools get more sophisticated in their rendering capabilities (the latest crop of zooming browsers is very cool), there is still only so much you can see at once on the screen. Even when I zoom out until I can just barely read the text on the screen, I still find myself panning back and forth just to read a single text flow in a document. Attempts to reflow the document often break the layout and make the document difficult to understand.

This is all the result of what I call “Mount Everest development.” Many tools are ported to mobile platforms just “because it is there.” It may be clever and a testimony to someone’s development skills, but it is ultimately useless.

When IBM PCs first became popular, one of the most important things you could buy was an Irma board. It added the coax connector and software that let your PC emulate a 3270 terminal. Migrating a 3270 mainframe display onto this new platform was useful, but hardly scratched the surface of what the device could really do.

The real breakthrough on these devices occurs when clever ways to exploit the form-factor emerge. Instead of dragging the tools of the past onto the platforms of the future, we need to figure out how to use these platforms in ways we never previously imagined.

In The Beginning… January 24, 2008

Posted by Chuck Musciano in Random Musings, Technology.Tags: Computing, History

add a comment

For me, my computing career started in the fall of 1975. Up to that point, my natural affinity for math and science seemed to be leading to the glamorous world of nuclear physics. Who wouldn’t want to spend their days building bombs and reactors? It was hard to imagine anything more exotic or enticing.

Then I saw it. Tucked in the corner of my high school’s mezzanine was the coolest device I had ever laid eyes on: an ASR33 teletype. Noisy, oily, built like a tank, it was attached to an acoustical modem that, in turn, dialed out to nearby Princeton University. Our high school had an account on the University system that could be used to run BASIC programs. My math teacher, Mrs. Horvath, taught simple computer programming to some of her higher classes. She invited me to try it, and from the moment my fingers touched the keyboard, my life was changed.

Then I saw it. Tucked in the corner of my high school’s mezzanine was the coolest device I had ever laid eyes on: an ASR33 teletype. Noisy, oily, built like a tank, it was attached to an acoustical modem that, in turn, dialed out to nearby Princeton University. Our high school had an account on the University system that could be used to run BASIC programs. My math teacher, Mrs. Horvath, taught simple computer programming to some of her higher classes. She invited me to try it, and from the moment my fingers touched the keyboard, my life was changed.

My first program allowed you to type in three numbers, after which it would print out the largest of the three. The whole idea of programming, of figuring out sequences of instructions to accomplish some larger goal, was absolutely fascinating. Although I wasn’t in a class that was actually learning to program, Mrs. Horvath let me use the system after school. I’d spend hours writing programs for everything I could think of.

The ASR33 was wonderful. It printed in uppercase only, on rolls of yellow teletype paper. The print carriage used a cylindrical type head that pounded out the characters, and a piston and cup arrangement caught the printhead as it slammed to left on each carriage return. You could lose a finger if you stuck your hand inside at the wrong moment. When you sat down at that terminal, you knew you were using a computer!

The ASR33 had a paper tape punch/reader, which let you punch your programs to tape without dialing in, saving connect charges. After punching your tape, you’d dial in, feed the tape back in, and quickly enter and save your program. Thus the acronym ASR: the paper tape allowed for Automatic Send Receive. (The lesser model, the KSR, allowed only real-time Keyboard Send Receive).

The ASR33 had a paper tape punch/reader, which let you punch your programs to tape without dialing in, saving connect charges. After punching your tape, you’d dial in, feed the tape back in, and quickly enter and save your program. Thus the acronym ASR: the paper tape allowed for Automatic Send Receive. (The lesser model, the KSR, allowed only real-time Keyboard Send Receive).

I can still recall the smell of the ASR33, and the separate, slightly oily smell of the paper tape. The big round keys would travel at least a quarter-inch when you pressed them, and touchtyping was pretty much out of the question. Beyond the chunka-chunka-chunk sound of printing, the only other noise it made was a real bell that would chime. None of this mattered: it was a real computer, and it ran real programs.

I wrote all sorts of programs, from maze generators to a Battleship game to graphing tools and even a program that drew hydrocarbon molecules after you gave it the chemical formula (I’d like to see today’s web hotshots do that on a teletype!). I built a database that tracked our wrestling team’s statistics and another program that generated random music. You couldn’t play the music on the ASR33, of course, but it did print out the complete score so that you could then play it on a piano.

The system also handled FORTRAN and PL/I programs, and I dabbled a bit in those languages as well. Is there anyone left who can still recall typing “PROC OPTIONS(MAIN)” to start out their program?

I have written millions of lines of code since then, for more systems than I can count, but the joy of using that first system still resonates in my soul. I knew then that I’d be playing with computers for the rest of my life. I wonder if those who are just starting in our industry today have similar memories of their first machines. In some ways, the best part of that ASR33 was that it was so primitive; getting it to do anything was a major accomplishment. It’s so easy to do cool things with systems today; is the experience less fun and inspiring as a result?